Ecosystems Services – what are they and why are they so important?

By Arend Hoogervorst

Ecosystem Services?

Ecosystem services are services

provided by natural capital (“Nature” or “the environment”- see Explanations

below) that support life on earth and are essential to the quality of human

life and the functioning of the world’s economies. For example, forests help

purify air and water, reduce soil erosion, regulate climate and recycle

nutrients.

Ecosystem

services are the benefits provided by ecosystems that contribute

to making human life both possible and worth living. Examples of ecosystem

services include products such as food and water, regulation of floods, soil

erosion and disease outbreaks, and non-material benefits such as recreational

and spiritual benefits in natural areas. The term ‘services’ is usually used to

encompass the tangible and intangible benefits that humans obtain from

ecosystems, which are sometimes separated into ‘goods’ and ‘services’.

The use of the term “natural

capital” is developed from “capital” used in economics and human financial

systems. It is a means of drawing human and environmental systems closer

together and to encourage more integration in thinking and practice. Some have

said that ecosystem services thinking is a means of placing a monetary value on

“the environment”, although the mechanisms are currently imperfect and

incomplete.

Explanations

Ecosystems

In

terms of “Nature”, an ecosystem is a biological community of interacting

organisms and their physical environment; for example, “the marine ecosystem of

the northern Gulf had suffered irreparable damage”. In broader, “non-natural”

terms, an ecosystem is a complex network or interconnected system; for example,

“Silicon Valley’s entrepreneurial ecosystem”.

Ecosystem

services

Ecosystem services are the conditions and processes through which natural ecosystems, and the species that make them up, sustain and fulfill human life. They maintain biodiversity and the production of ecosystem goods.

Natural

capital

Natural

capital can be defined as the world’s stocks of natural assets or environmental

resources which include geology, soil, air, water and all living things. It is

from this natural capital that humans derive a wide range of services, often

called ecosystem services, which make human life possible.

Built

capital

Built

Capital is defined as any pre-existing or planned formation that is constructed

or retrofitted to suit community needs. (In other words, it is any human-made

environment.)

Human

capital

Human

capital is the stock of knowledge, habits, social and personality attributes,

including creativity, embodied in the ability to perform labour so as to

produce economic value.

Social

capital

Social

capital broadly refers to those factors of effectively functioning social

groups that include such things as interpersonal relationships, a shared sense

of identity, a shared understanding, shared norms, shared values, trust,

cooperation, and reciprocity.

Sustainability

Sustainability

means that a process or state can be maintained at a certain level for as long

as is wanted.

Sustainable

development

Sustainable

development is development that meets the needs of the present without

compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

The concept of ecosystem services

considers the usefulness of nature for human society. The economic importance

of nature was described and analysed in the 18th century, but the term,

ecosystem services, was only introduced in 1981 through the work of ecologists

such as Paul Erlich and HE Daly. In the latter part of the 20th

Century, the observation of significant and extended damage to ecosystems caused

by human impacts began to highlight the ‘real’ role of ecosystem services,

resulting in more study and focus.

Be aware that ecosystems have

different functioning levels (See figure 1) and for the sake of clear explanation,

this article focuses on high level discussion. The figure demonstrates the

different functioning levels that occur in typical ecosystems.

Figure 1: levels of organisation in an ecosystem

Source: eSchooltoday

Ecosystem Capital

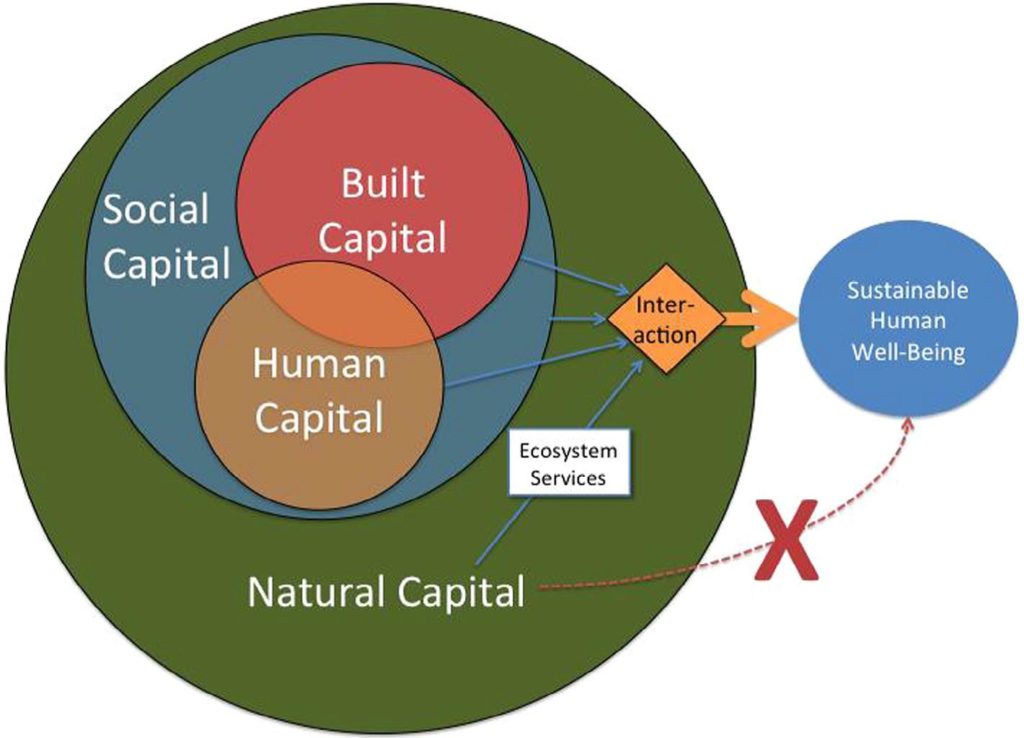

Figure 2 (developed by Costanza

et. al.) below illustrates the interrelationships between the different types

of capital in the environment. Built Capital

represents the built environment (human and non-human), Human Capital represents the knowledge, habits, social and

personality attributes, including creativity, embodied in the ability to

perform labour and Social capital

represents the factors of effectively functioning social groups that include

such things as interpersonal relationships, a shared sense of identity, a

shared understanding, shared norms, shared values, trust, cooperation, and

reciprocity, all of which are contained within Natural Capital. The interaction

of some or all of these different forms of capital contributes towards the goal

of sustainable human well-being and is enhanced by ecosystem services.

Figure 2 – Interrelationships

between different types of Natural Capital

Ecosystem Services

Classification

Ecosystem services have been classified in various ways,

including:

- ‘Functional

groupings’, such as regulation (controls e.g. climate), carrier (e.g.

pollination and seed transport), habitat, production (e.g. food), and

information services

- ‘Organisational

groupings’, such as services associated with certain species that regulate

external inputs into a system, and those related to the organisation of biological

entities

- ‘Descriptive

groupings’, such as renewable resource goods, non-renewable resource goods,

physical structure services, biotic services, biogeochemical services,

information services, and social and cultural services.

Functional Grouping

The most widely adopted

classification is the ‘functional grouping’ where ecosystem services are

divided into four categories. Some

overlap occurs between categories but the four main groupings include:

- Provisioning

services which are the products that are obtained from ecosystems, such as:

genetic resources, food, water, fuel, bio-chemicals, fibre, natural medicines,

pharmaceuticals, and building materials.

- Regulating

services which are the benefits obtained from the regulation of ecosystem

processes. These include: climate regulation, water regulation and

purification, air quality maintenance, erosion control, waste treatment,

regulation of human diseases, biological control, pollination, and protection

from extreme weather and climatic events.

- Cultural

services which are nonphysical benefits that humans obtain from ecosystems

through spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, reflection, recreation,

and aesthetic experiences. These

services are connected to human behaviour and values, as well as institutions

and patterns of political, social and economic organisation. Cultural services include: cultural

diversity, spiritual and religious values, knowledge systems, educational

values, inspiration, aesthetic values, social relations, sense of place,

cultural heritage values, and tourism.

Spaceship Earth

It

is important to recognise that humans are integral elements of global

ecosystems and that dynamic interactions take place between them and other

parts of ecosystems. The ever changing human condition drives ecosystem change

directly and indirectly, thereby bringing about changes in human well-being.

Concurrently, economic, cultural and social factors, independent from

ecosystems, influence the human condition, and natural forces shape ecosystems.

Ecosystem

services influence human well-being, which is assumed to possess multiple

constituents, including: basic materials to support a good quality of life,

such as secure and adequate livelihoods, ample food, shelter, clothing, and

access to goods; health, including well-being, a healthy physical environment,

such as clean air and water; good social relations, which includes social

cohesion, mutual respect, the means to assist others and provide for children;

security, including secure access to resources, personal safety, and protection

against natural and human induced disasters; and freedom of choice and action,

which are the opportunities that enable individuals to achieve what they value

doing and being.

The

earth is not an “infinite resource” and it is important to recognise that

polluting or damaging our “Spaceship” or not respecting its needs and

limitations could have significant impacts upon its ability to sustain our

lives in the future. As the earth’s human population continues to grow

exponentially, future problems affecting the survival of human beings can be

expected as various ecosystems services begin to break down, fail and become

less sustainable.

Ecosystem Disservices

Ecosystem management, in some

cases, may lead to possible ecosystem disservices. Examples of disservices can include:

increased prevalence of allergens; promoting invasive species; hosting

pathogens or pests; inhibiting human mobility or safety; bringing about

cultural and psychological effects that negatively impact human well-being; or

increasing the necessity for using natural resources (i.e. water) or chemicals

(i.e. pesticides and fertilisers).

Supporting Services

Supporting services are those

which are necessary for the production of all other ecosystem services. They differ from other services as their

impacts on humans are indirect, or occur over a long time period. Some services, such as erosion control, can

be categorised as a supporting and regulating service (depending on the time

scale and immediacy of their impact on humans).

Examples of supporting services include: production of atmospheric

oxygen (through photosynthesis), primary production, soil formation and

retention, nutrient cycling, water cycling and provisioning of habitat.

Direct and Indirect

Services

Some ecosystem services involve

the direct provision of material and non-material goods to people and depend on

the presence of particular species of plants and animals, for example, food,

timber, and medicines. Other ecosystem services arise directly or indirectly

from the functioning of ecosystem processes. For example, the service of

formation of soils and soil fertility that sustains crop and livestock

production depends on the ecosystem processes of decomposition and nutrient

cycling by soil micro-organisms.

Stricter Focus

Some scientists have advocated a

stricter definition of ecosystem services as only the components of nature that

are directly enjoyed, consumed, or used in order to maintain or enhance human

well-being. Such an approach can be useful when it comes to ecosystem service

accounting and economic valuation. This is because some ecosystem services

(e.g. food provision) can be quantified in units that are easily comprehensible

by policy makers and the general public. Other services, for example, those

that support and regulate the production levels of crops and other harvested

goods, are more difficult to quantify. If a definition based on accounting is

applied too strictly there is a risk that ecosystem service assessment could be

biased toward services that are easily quantifiable, but with inadequate

consideration of the most critical ones for human well-being.

Debate and

Publications

The concept of ecosystem services

has prompted an increasing number of academic publications, international

research projects, and policy studies. It is a subject of intense debate in the

global scientific community, from the natural to social science domains. It is

also used, developed, and customised in policy debates and considered, if in a

still somewhat sceptical and apprehensive way, in the “practice” domain—by

nature management agencies, farmers, foresters, and the corporate world. This

process of bridging evident gaps between ecology and economics, and between

nature conservation and economic development, has also been noted in the

political arena, including in the United Nations and the European Union.

Areas of Discussion

The concept appears in four major discussions:

- Academic:

the ecological versus the economic dimensions of the goods and services that

flow from ecosystems to the human economy; the challenge of integrating

concepts and models across this paradigmatic divide;

- Social:

the risks versus benefits of bringing the utilitarian argument into political

debates about nature conservation (Are ecosystem services good or bad for

biodiversity and vice versa?);

- Policy

and planning: how to value the benefits from natural capital and ecosystem

services (Will this improve decision-making on topics ranging from poverty

alleviation via subsidies to farmers to planning of grey with green

infrastructure to combining economic growth with nature conservation?); and

- Practice:

Can revenue come from smart management and sustainable use of ecosystems? Are

there markets to be discovered and can businesses be created? How do taxes

figure in an ecosystem-based economy? The outcomes of these discussions will

both help to shape policy and planning of economies at global, national, and

regional scales and contribute to the long-term survival and well-being of

humanity.

Final Thoughts

“Ecosystems services” is a

concept which may help to bridge the gap between the traditional economists

(“Air soil and water are “free” goods which must be freely accessible to all.”)

and multi-disciplinary decision makers (“There’s no such thing as a “free”

lunch.”). After 20 years, the concept is still being hotly debated at many

levels. It has perhaps resulted in the beginnings of consensus that there is need

for a new economic paradigm which puts “Nature” at its core. It certainly is

beginning to walk hand-in-hand with the “People, Planet and Prosperity” themes

that emerged from the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) held in

Johannesburg in 2002 and the subsequent UN Sustainable Development goals. There

is no doubt that current economic systems and thinking needs to be changed to

cope with the 21st century issues that need to be faced.

Note

This article is designed to

provide basic explanations and stimulate thought rather than going into excessive

detail. Other authors have written tomes on ecosystem or nature services and

there are many academic articles of different viewpoints on this subject. For

the sake of brevity, this author has applied his view on certain elements of

the topic for which he takes full responsibility.

References

Braat, L.C., Mar 2016. Framing

Concepts in Environmental Science, Policy, Governance, and Law, Management and

Planning, Sustainability and Solutions, Online Publication.

Brundtland Commission, 1987.

“Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development”. United Nations.

Daly, G.C., 1997. Nature’s

Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems. Island Press.

Costanza, R., de Groot R., Braat

L., Kubiszewski I., Fioramonti L., Sutton P., Farber S., and Grasso M., 2017.

Twenty Years of ecosystem services: How far have we come and how far do we

still need to go? Ecosystems Services, 28, 1-16.

De Groot, R.S., Wilson, M.A.

& Boumans, R.M.J., 2002. A typology for the classification, description and

valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecological Economics, 41,

393–408.

Norberg, J., 1999. Linking

Nature’s services to ecosystems: some general ecological concepts. Ecological

Economics, 29, 183–202.

Moberg, F and Folke, C., 1999.

Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems. Ecological Economics, 29,

215–233.

Tyler Miller, G & Spoolman,

S.E., 2018. “Living in the Environment”. 19th Edition, Cengage Learning.